This article was written by Gerhard Andrey and Philipp Egli Jung and was originally published in Zeitschrift für Führung und Organisation, edition 6 2016. Translation to English: Liip.

New approaches to company management are usually discussed positively in the media. A glance at the comment columns of two recently published online publications on Holacracy shows, however, that there are some critical voices [1], most comments of which may be summed up to "Old wine in new bottles". However, the commentators usually try to grasp what is not quite graspable through the lens of the classic concepts of corporate management. That's why hierarchical thinking shimmers through this criticism again and again.

Hierarchical organizations have achieved great things, but are reaching their limits in today's complex world. This is also a central point which is repeatedly mentioned in the discussion between Laloux and Robertson [2]. Holacracy does not mean that there is no structure, no rules or no order anymore – on the contrary: the principle of order is no longer based on the power structure, but the way work is done in a company. In addition, this structure is no longer static, but is being constantly further developed by all persons working in the company.

Initial situation at Liip

Liip is one of the leading Swiss companies in the field of web and mobile application development. There has always been efforts at Liip to keep hierarchies as flat as possible where they seemed unavoidable.

In the IT industry and in the agency world, a company's ability to innovate is a primary factor of success. Project work demands specific organisational answers. Liip being located in two linguistic and cultural areas– in the French and German parts of Switzerland – added a level of complexity. The previous system with flat hierarchies no longer scaled.

For these reason, the management transferred in 2013 a large part of the responsibility to the teams, by making them cross-functional. This means that all teams have all the necessary resources and skills to carry out their daily work on board. Excepted from this are some transversal functions such as Personnel Administration, Finance and Communication, which advise the teams. The teams themselves decide on their strategy, customer acquisition, technologies used and the hiring of new employees.

However, the transversal functions were not yet clearly defined. They were often paired with a management function. This led in the mid-term to a communication problem. Many employees expected the management to make certain decisions (despite far-reaching self-determination), but the management did not see this as their responsibility at all. Conversely, the teams felt constrained by the decisions of the management or of transversal functions.

First steps with Holacracy

A further expansion of hierarchy levels was however out of question. At the end of 2015, we decided to experiment with Holacracy. A small group of employees as well as the management attended the Holacracy Practitioner training and immediately started implementing Holacracy.

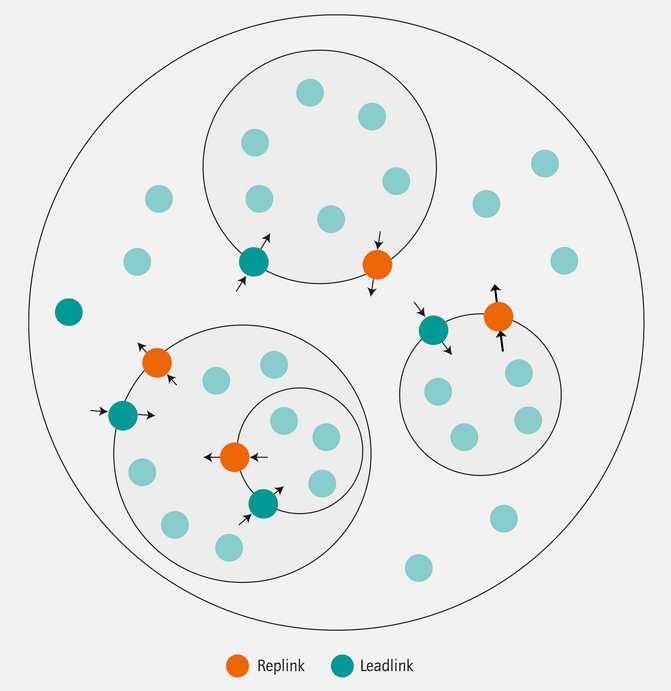

The Holacracy Constitution, currently available in version 4.1, describes a whole system. The central components of Holacracy are roles and circles. They are the actual holons: self-sufficient and capable of acting in themselves, but also part of the whole (Fig. 1). Each circle and each role has a purpose, accountabilities, domains and policies. Circles and roles differ in that a circle can contain further roles. In addition, circles also accommodate the standard roles: Lead Link, Rep Link, Facilitator and Secretary. They ensure the base functions of the circle. The communication between the circles is clearly regulated and includes the principle of separation of powers. The Rep link brings information from the circle to the outer circle, the Lead link brings information from the outer circle to the sub-circle (Fig. 1). The Secretary documents the decisions and the structure of the circle and assists in questions of interpretation of the Constitution. The Facilitator is the master of ceremonies and moderates the meetings. Holacracy knows two types of meetings: employees can work on the organization in Governance meetings, whilst operational and day-to-day business are handled in Tactical meetings.

Holacracy does not offer magic recipes on how to solve a particular organizational problem, but only structural elements (roles and circles with responsibilities) that can be used to map an organization. Brian Robertson compares Holacracy with an operating system in various places [7]. The implementation of a specific organizational problem would be an application according to this logic.

Work in the company and on the company

At Liip, we decided to map the existing structures without optimizing them beforehand. The optimization should then take place in the process of Holacracy itself. The joint-stock company forms the outermost circle, it is the legal shell of the enterprise. The purpose of the external circle is to comply with the obligations of an AG under Swiss law and to represent the core values of the company.

The "General Company Circle" is located within this circle. It contains the roles and circles of the company. The individual locations are organised as circles and are therefore largely independent. They include the production teams. The transversal functions General Administration, Personnel Administration, Finances and Communication & Marketing are also organised as circles. These circles operate across locations. Where necessary, there are roles within these circles that are multiple and have a local focus. Another group of roles and circles are the consultants or process optimizers. For example, there is a circle there that takes care of the implementation of Holacracy in the company, or business developers with a great deal of experience who coach customer-oriented profiles. Currently there are 30 circles and 340 roles in the company. So the output is really remarkably detailed. But who built this structure? In Holacracy every employee is a partner and self-determined. He may make any decision and perform any action within the scope of his roles or within the scope of the company's purpose, as long as he does not violate the domain of another role or another circle. To exchange information and plan projects and actions, he uses the Tactical meetings or directly exchanges information with other roles.

If an employee feels during his work that something can be improved, then he experiences a tension. Brian Robertson defines them as a “gap between how things are and how they could be” [8]. Robertson considers the employees' sense of recognizing improvement potential from their daily work to be one of the most valuable resources of a company [9]. If the tension can be solved by information exchange, a project or a concrete action, this takes place directly in the daily business or in a Tactical meeting. If the change affects the structure, i.e. role, responsibility, circle, domain or policy, it is resolved in a Governance meeting. In this way, the structure constantly adapts to the circumstances, optimising itself, so to speak.

The trough of disappointment

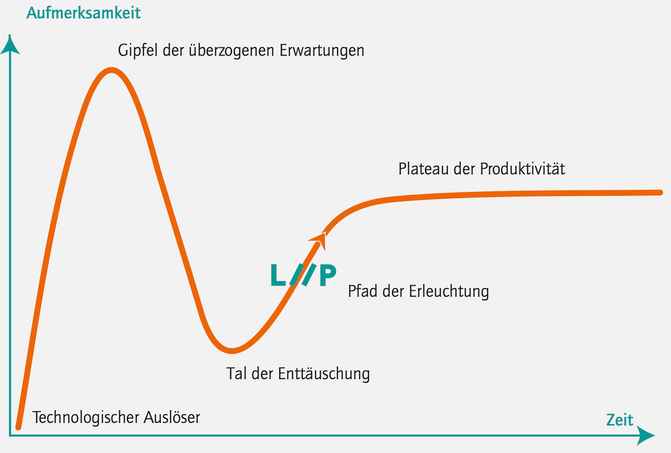

The experiment was limited to six months. After the initial euphoria, however, disillusionment quickly set in. The problems were of a cultural nature and the fronts were stuck. To speak with the Gartner Hype cycle (see fig. 2): we were in the Trough of disullusionment. A survey in which everyone could comment on the Holacracy experiment revealed positive voices as well as enough negative ones that needed to be taken seriously: the system was perceived as too bureaucratic or too hierarchical. Important people are suddenly no longer involved in the meetings. The system is cold and impersonal. The meetings last too long.

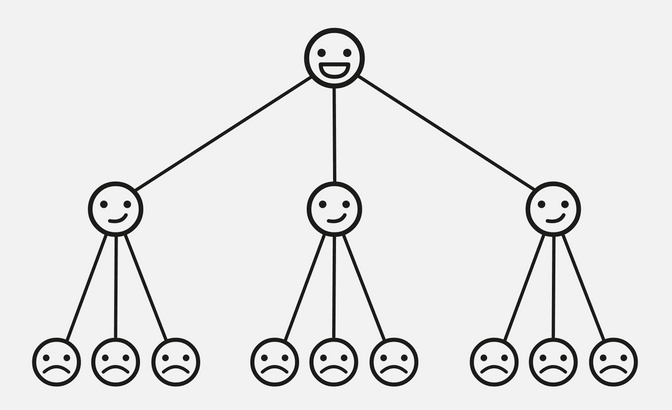

These reactions are probably also connected with the fact that flat hierarchies already existed at Liip before the introduction of Holacracy. The positive effect of self-determination has thus been greatly weakened. A colleague coined the term "do-acracy" in this context. Or to put it another way, the following principle applied to Liip even before the introduction of Holacracy: “Power to the doers”. Furthermore, Holacracy may assume too strongly that a company was previously organized hierarchically (cf. Fig. 3). In such a company, employees from the lower hierarchical levels experience the right to have a say as a liberation. In a company like Liip, which already had flat hierarchies and little structure, this effect is less visible. On the contrary: since Holacracy has a great deal of structure, some consider it bureaucratic or even hierarchical.

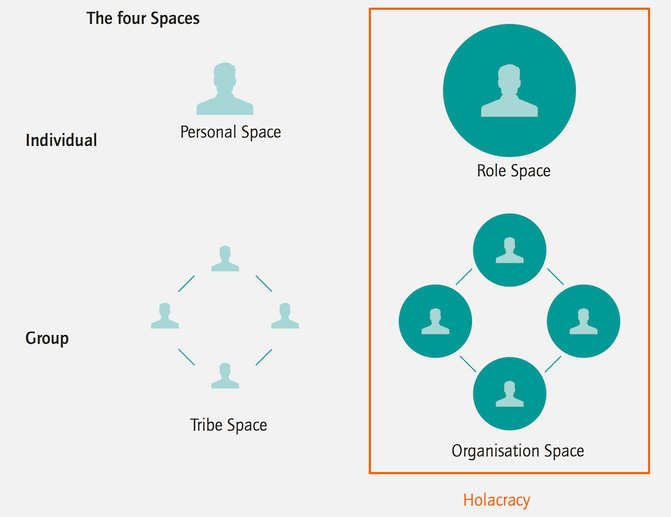

Employees at Liip have always assumed a great deal of entrepreneurial responsibility. This enabled people to "set themselves in the limelight" and take on a role model function with their personality. With the introduction of Holacracy, this is now a thing of the past. In Holacracy, a clear distinction is made between the personal space and the space of the role (cf. Fig. 4). People only act in their roles. In a company with strong social cohesion, this at first seems strange.

Benefits

However, this rigid structure also creates the basis for transparency and the avoidance of duplication. And that's exactly where the benefits lie: a company with five locations and over 150 employees in two linguistic and cultural areas needs structure - not a rigid structure, but more a structure that adapts to the circumstances on a daily basis. And Holacracy creates this benefit.

In addition, the transversal functions are better regulated. The teams know what they can expect and from which role they can expect it. If something is unclear, it can be clarified in the governance process. This leads to a large relief for the persons who are active in these functions.

Decisions can be made today without finding consensus at the relationship level or securing oneself throughout the company. This is liberating and significantly shortens decision-making processes after only six months of practice. In the marketing department, for example, the weekly coordination meeting was reduced from an initial hour or more before the introduction of Holacracy to 15 to 30 minutes. Moreover, the company is now really organized without a classical management and hierarchical thinking; a goal we have been working towards for a long time.

Learnings

When we introduced Holacracy, we had to painfully realize that the extreme separation of person and role leads to problems. This was not taken sufficiently into account when Holacracy was introduced. In the meantime, however, we have taken appropriate measures: above all, it is important to create spaces in which people can speak again. How do they feel about the new structure, where do they have difficulties or questions?

Holacracy is not easy to understand and requires a lot of thought and concentration from all partiesinvolved. And it's about breaking old patterns of behavior. If the boss used to be to blamed if something didn't work out, you are now responsible yourself. In the past, it was possible to agree with the opinion of colleagues who set an example, but today you have to think for yourself. According to Berners' transactional analysis, you have to break away from unhealthy parent-child patterns and grow up. This also applies to former middle managers, of course. Robertson uses the archetypes from the drama triangle: the savior, the persecutor or the victim. They are popular roles and vehicles of self-definition among employees and management [10]. Working with Holacracy is the work of each individual on himself. There can be no integral company without people who set out to think holistically. And that also means putting one's own ego back in the company.

References

[1] Vgl. Hockling, S.: So kommen Mitarbeiter aus der Hierarchie heraus. In: Die Zeit Online. (http://www.zeit.de), http://tinyurl.com/nh3tezt (letzter Zugriff: 22.7.2016); Saheb, A.: Arbeiten ohne Chef und Hierarchie. In: NZZ Online, (http://www.nzz.ch), http://tinyurl.com/jze4yw5 (letzter Zugriff: 22.7.2016).

[2] Cowan, C.: Five Critiques of Holacracy – Brian Robertson and Frédéric Laloux discuss the case against alternative governance models, (https://blog.holacracy. org), http://tinyurl.com/z8upfwb (letzter Zugriff: 24.7.2016).

[3] Koestler, A.: The Ghost in the Machine, Neuauflage, London 1989.

[4] Wilber, K.: Eine kurze Geschichte des Kosmos, Frankfurt a. M. 1997, S. 40 ff.

[5] Wilber, K.: Integrale Vision: Eine kurze Geschichte der integralen Spiritualität. München 2009, S. 112 f.

[6] Laloux, Frederic: Reinventing Organizations: Ein Leitfaden zur Gestaltung sinnstiftender Formen der Zusammenarbeit, München 2015.

[7] Vgl. Robertson, B. J.: Holacracy: The New Management System for a Rapidly Changing World, New York 2015, Kapitel 1.

[8] Robertson, B. J.: Holacracy, a. a. O.

[9] Robertson, Brian J.: Processing Tensions, (https://blog.holacracy.org), http://tinyurl.com/jgl9nmt (letzter Zugriff: 22.7.2016).

[10] Vgl. Laloux, F.: Reinventing Organizations, a. a. O., S. 145 f.